USA TODAY

Despite NCAA regulations prohibiting sports wagering for money, 26 percent of male student-athletes report doing just that, with 8 percent gambling on sports at least monthly. Of particular concern is the culture surrounding golf, where on-course wagering is considered a normative aspect of the experience.

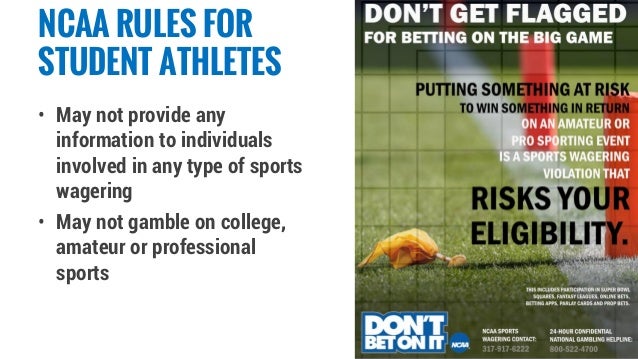

While sports wagering in the US has skyrocketed over the past several months, perhaps one issue has been overlooked that is now drawing some concern. Last Thursday an NCAA official voiced opinion regarding sports betting on the performance of individual college athletes while suggesting that gambling regulators consider restrictions on such wagers, known as proposition wagers, to protect the. Sports Wagering Activities NCAA legislation prohibits SDA student-athletes and staff members from gambling or wagering on any sport (amateur, professional, or otherwise) in which the NCAA conducts a championship or bowl game. As an NCAA student-athlete, you may not participate in gambling or wagering, including but not limited to the following: placing, accepting or soliciting a wager of any type with any individual or organization on any intercollegiate, amateur or professional team or contest (this includes an action taken on a student-athlete’s own behalf or on.

College athletes would gain new and significant abilities to make money from the use of their name, image and likeness, beginning Aug. 1, 2021, under a series of specific proposals for Division I rules changes unveiled Friday.

However, the proposed rules changes would give schools discretion to prevent athletes from having deals that are deemed to conflict with existing school sponsorship arrangements. These restrictions could put the NCAA at odds with the provisions of laws that have been passed by four states and are set to take effect in the coming months and years.

The proposed rules changes were listed in a document outlining changes that are scheduled to be voted on by the NCAA Division I Council during the association’s convention in January. The Council, comprised of representatives of the various conferences, is the primary rules-making body for the association’s top-level schools.

Conferences can offer amendments to any of the proposed rules changes until Dec. 15, meaning the changes proposed Friday could be altered further before they are voted on. Meanwhile, bills relating to this topic remain pending in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

The basic contours of the NCAA's proposed changes have been discussed previously by association and college sports officials, but this is the first time the changes have been put into fully formed prospective rules.

The rules changes being proposed also generally would apply — at least from the NCAA's perspective — to prospective college athletes. The document unveiled Friday says: 'This model would ensure consistency and clarity for prospective student-athletes' and minimize 'the risk of prospective student-athletes entering into agreements or relationships before full-time enrollment that could render them ineligible when they become student-athletes.'

How this would connect with various current state high school athletic association rules remains to be seen.

The NCAA proposals also call for college athletes and prospective athletes engaging in name, image and likeness business activities to disclose those activities to 'an independent third-party administrator' that is not detailed further.

But in citing the need for such an entity, the new document acknowledges 'boosters may be the most likely sources of opportunities for student-athletes to engage in name, image and likeness activities. Student-athletes should be permitted take advantage of legitimate opportunities, even if the source of the opportunity comes from a booster of the institution.'

College athletes also would be allowed to make money for signing autographs and for providing instruction lessons. They would be allowed to sell memorabilia once they have completed their eligibility. They also would be able to use crowdfunding sites to raise money for educational expenses that exceed the cost of attendance.

More broadly, according to the proposals, athletes would be allowed to use their name, image and likeness (NIL) “to promote … athletically and nonathletically related business activities (e.g., products, services, personal appearances).” Athletes would be allowed to mention their involvement in sports and the name of the school they attend. However, they would not be allowed to use any institutional marks, such as logos.

Specifically, the proposals say athletes would be allowed “to advertise or promote the sale or use of a commercial product or service, provided there is no institutional involvement in the arrangement.”

Athletes would be allowed to use what the proposals call 'professional service providers' — but not school employees or contractors — to seek and negotiate deals, but the athletes will face requirements concerning disclosure of their NIL activities and other significant restrictions:

• They would not be allowed to engage in NIL activities involving a commercial product or service that conflicts with NCAA legislation. That means they cannot be involved with sponsorships related to sports betting or banned substances.

• Athletes’ NIL could not be used by “an athletics equipment company or manufacturer to publicize [that] the institution's athletics program uses its equipment.” This would seem to heavily narrow or foreclose an athlete's ability to have a sponsorship deal with a shoe and apparel company that has a contract with the athlete’s school. California's NIL law, set to take effect Jan. 1, 2023, would allow athletes to have deals with shoe and apparel companies that sponsor their respective schools.

• Schools would be able to prohibit an athlete from being involved in NIL activities that “conflict with existing institutional sponsorship arrangements. An institution, at its discretion, may prohibit a student-athlete’s involvement in name, image and likeness activities based on other considerations, such as conflict with institutional values, as defined by the institution.”

The schools would be required to have policies that establish the NIL activities in which athletes may or may not engage, and they would have to provide those policies to prospective student-athletes.

This has the potential to heavily narrow commercial opportunities available to athletes, as many schools have sponsorships with a broad array of companies in many brand categories, from shoes and apparel to local car dealerships, banks and restaurants.

This restriction is where the conflict with state laws could occur. Recently enacted statutes in California, Colorado, Nebraska and New Jersey include provisions that would prevent athletes from having an endorsement contract that would conflict with a school contract. But those states’ laws also say that schools cannot have contracts that prevent athletes from using their NIL for a commercial purpose when the athlete is not engaged in official team activities.

Number Of Ncaa Student Athletes

(Florida also has a college-athlete NIL law that is set to take effect July 1, 2021, but that law does not have the additional provision regarding athletes' activities outside official team settings.)

In other words, those states’ laws would appear to prevent a school aligned with one company from preventing its athletes from having a deal with a competing company, as long as the athlete is keeping the promotional activities separate from official school activities.

Findings:

- Overall rates of gambling among NCAA men have decreased. Fifty-five percent of men in the 2016 study reported gambling for money within the past year, compared to 57% of respondents in the 2012 study and 66% in 2008. As in the general population (college-aged and otherwise), women engage in nearly all gambling activities at much lower rates than men. Over the 12-year period studied, participation in most gambling activities decreased among all student-athletes despite the expansion of land-based and online gambling opportunities during this time.

- However, in contrast to activities such as poker or online casino games, sports wagering remains popular among student-athletes. In 2016, 24% of men reported violating NCAA bylaws within the previous year by wagering on sports for money (9% reported wagering on sports once per month or more). These rates are just slightly lower those seen in the 2008 and 2012 surveys. About 5% of current NCAA women reported wagering on sports in the past year.

- Most of the gambling and sports wagering behaviors of student-athletes involve low stakes. Among student-athletes who have ever gambled for money, the largest reported one-day loss is less than $10 for nearly one-third of men and more than onehalf of women. Only 35% of men and 13% of women gamblers have ever lost more than $50 in a day. Of the student-athletes who have ever wagered on sports, only 21% of men and 5% of women reported losing more than $50 in a day. Most fantasy sports and basketball pool participation among student-athletes involves similarly low amounts.

- That said, gambling and sports wagering can lead to significant well-being issues for some student-athletes. Just under 2% of men participating in the 2016 survey (along with a smaller percentage of women) met standard diagnostic criteria for problem gambling. Four percent of men who had gambled in the past year reported one-day gambling losses of $500 or more. Student-athlete gambling debts are a wellbeing concern, but also a worry for potential vulnerability to outside gambling influences.

- Gambling and sports wagering behaviors are initiated long before college for many NCAA student-athletes. Thirty-one percent of NCAA men and 14% of NCAA women gamblers had their first such experience prior to entering high school. Only 12% of men and 31% of women in the 2016 survey who had ever gambled indicated that they first gambled in college. Among those student-athletes who have ever bet on sports, 90% of men and 82% of women placed their first bet before entering college. Although playing cards for money was the most common gambling entry point for current NCAA men, we are increasingly seeing sports wagering being cited as their first gambling activity.

- There are many different sports on which student-athletes report wagering, but the majority of sports betting is focused on a few sports. The NFL remains the top sports wagering target for both men (65% of those who bet on sports in the past year) and women (44%), followed closely by college basketball (primarily tournament pools or bracket contests). The NBA and college football round out the top four targets for both men and women.

- Technology continues to change how gambling and sports wagering occur. Most student-athlete sports betting occurs among friends, family and teammates. However, the next most popular method for placing a sports bet is not at a casino / sports book or a via a traditional bookie, but electronically through an Internet site or an application on one’s phone or tablet. One-third of the men and 15% of the women who reported wagering on sports in the 2016 survey placed bets electronically. In addition, a number of student-athletes continue to report engaging in some form of simulated gambling activity via social media sites, videogame consoles or mobile devices. These games are being increasingly marketed toward youth, and the line between gaming and gambling via social media sites is quickly disappearing in many countries.

- There are contest fairness concerns around sports wagering technological enhancements. We continue to have concerns that wagering enhancements such as live in-game betting (odds generated in real-time for participants to bet on various aspects of a game as it unfolds) could present increased opportunities to profit from “spot fixing” a contest (just a single mid-game event or portion of a contest needing to be fixed for a bet to pay off) as has been uncovered recently in a number of international sports leagues. Spot fixing is generally seen as easier to undertake and harder to detect than manipulating a final contest outcome. Thirteen percent of the NCAA men who wagered on sports in the past year engaged in live in-game betting. An additional technological concern is the proliferation of websites that offer betting lines on NCAA sports outside of men’s basketball and football, including non-Division I contests.

- Fantasy sports continue to be popular among student-athletes. However, it appears that daily fantasy games have not led to increases in the number of student-athlete fantasy participants. Approximately 10% of NCAA women and onehalf of NCAA men have participated in free fantasy sports leagues. Twenty percent of men and 3% of women in the 2016 study reported having played (in violation of NCAA bylaws) in fantasy leagues with an entry fee and prize money during the past year. Both sets of rates are similar to what was seen in the 2008 and 2012 surveys. Although 11% of men and 2% of women surveyed in 2016 said they had recently played daily or weekly online fantasy sports contests for money, these participants overlapped substantially with those who reported playing season-long fantasy games. Note that the 2016 survey took place in proximity to a spike in advertising for such daily fantasy sites such as DraftKings and FanDuel.

- Student-athletes seem to be more attuned to outside sources looking for inside information. Division I men’s basketball and football players continue to be seen by gamblers as important potential sources for information that can provide a betting edge, whether that information comes indirectly (e.g., via a social media posting) or directly from the student-athlete. Perhaps as a result of campus educational efforts, the percentage of student-athletes reporting that they knowingly provided inside information remains lower than seen when these surveys began in 2004. In 2016, Division I football and basketball players reported being much less likely to post information via social media that could be useful to gamblers than was the case in 2012.

- It is difficult, if not impossible, to get a true gauge of illegal match fixing / point shaving behavior among student-athletes from these surveys. That said, we have generally seen decreases in student-athletes reporting the most concerning behaviors (betting on their own team, being asked to influence the outcome of a game, etc.) since 2004. One concerning number from 2016: Eleven percent of Division I football players and 5% of men’s basketball players reported betting on a college game in their sport (but not involving their team).

- Substantial divisional differences remain in gambling and sports wagering behaviors. Although their rates have dropped a bit over the course of the study, men and women in Divisions II and III continue to gamble and wager on sports (in violation of NCAA bylaws) at much higher levels than observed among Division I studentathletes. Whereas 17% of men in Division I reported wagering on sports in 2016, that percentage was 23% in Division II and 32% in Division III (for women, the Division I, II and III sports wagering rates were 3%, 4% and 7% respectively). The most likely reasons for these disparities are differences in educating student-athletes about NCAA sports wagering rules and perceptions that the rules (and potential issues of contest fairness) are solely a Division I concern.

- Some inroads appear to have been made with Division I golf student-athletes. However, there are still significant reasons to be concerned about gambling and sports wagering among golf student-athletes generally. Even outside the pervasive culture of on-course wagering in the sport, golf student-athletes (men in particular) across NCAA division are significantly more likely to engage in virtually every gambling activity assessed compared to other student-athletes. For example, 18% of men’s golfers report betting on sports (outside of on-course wagering) at least once per month versus 9% among other men. They are also two to three times more likely than other men to frequent casinos, play cards for money and play casino games on the Internet. Ten percent of Division I men’s golf participants reported betting on another team from their school, 16% said they know a bookie and 4% report knowing a studentathlete bookie at their school.

- Knowledge/understanding of NCAA wagering bylaws has risen since 2012. Among men and women within each NCAA division, more student-athletes reported in 2016 that they had received information on the NCAA sports wagering rules. Awareness of the rules is highest in Division I (76% among men and 82% for women) and lowest in Division III (68% for men, 64% for women). In addition to NCAA efforts to educate student-athletes (particularly those on the highest-profile teams) on sports wagering issues, many schools are making substantial efforts to provide their studentathletes with innovative programming and timely reminders about NCAA sports wagering bylaws.

- Changing attitudes about gambling and sports wagering is a difficult task. Fiftyfour percent of NCAA men and 31% of women currently report that they think sports wagering is a harmless pastime. These figures are substantially higher (76% and 61%) among those student-athletes who wager on sports. Half of men and one-quarter of women who bet on sports think they can consistently make a lot of money on the activity. They also feel that many others violate NCAA wagering bylaws and one-quarter believes coaches do not take these rules seriously. This last finding is important because student-athletes report that coach and teammate awareness/reaction is a significant factor in getting student-athletes not to wager.

- More than one-quarter of student-athletes are uncomfortable that people bet on college sports and more than half do not think gambling entities should advertise at college sporting events or during college sports telecasts. A slightly higher proportion (one-third) of Division I football and men’s basketball players report being uncomfortable with college sports wagering.

- Continued enhancements and innovations in educational programming are necessary to protect student-athlete well-being and contest fairness. As gambling opportunities and technologies continue to evolve and laws regulating the industry potentially change, it will be important that educational programming for student-athletes, coaches and athletics administrators be continuously evaluated. To be maximally effective, this programming needs to go beyond simply telling these groups not to gamble/wager, given the deepening normative nature of gambling and sports wagering in our society. These programs should assist all involved in college athletics to recognize risk factors associated with problem gambling, provide up-to-date information on the science and technology of gambling and sports wagering (e.g., betting lines are set using a great deal of data/research; gamblers can easily reach student-athletes through social media), and even promote strategies for discussing perceptions and normative expectations associated with gambling/wagering (e.g., being an athlete does not necessarily mean one has the insight required to make money wagering on sports, as many student-athletes believe). Many schools have developed their own educational initiatives and it is clear from the data that these local efforts are more effective than just receiving materials from outside entities like the NCAA staff. Above almost anything else, a typical student-athlete does not want to negatively impact his/her team. So, it is important that student-athletes from all three NCAA divisions fully understand not only the NCAA penalties for sports wagering, but also the potential negative outcomes for student-athlete and team well-being.

Study Background

- Over the course of four study iterations (2004, 2008, 2012 and 2016), more than 84,000 student-athletes across all three NCAA divisions were surveyed about their attitudes toward and engagement in various gambling activities, including sports wagering. This includes 22,388 in the 2016 study.

- Surveys were administered with the assistance of campus faculty athletics representatives (FARs), who were asked to survey up to three teams on each of their campuses. It is estimated that more than 60% of NCAA member schools participated on each occasion.

- Study protocols were designed to ensure the anonymity of participating studentathletes and schools.

- Analyses were limited to 22 sports (11 for men and 11 for women) that were adequately sampled in each NCAA division within each administration.

- A high data-cleaning standard was applied consistently to data from each administration. Data were then weighted in comparison to national participation rates within the sampled sports to create national aggregates.

- Study investigators are Dr. Thomas Paskus of the NCAA Research staff and Dr. Jeffrey Derevensky of McGill University.

Download the Trends in NCAA Student-Athlete Gambling Behaviors and Attitudes: Executive Summary

Read More > about Trends in NCAA Student-Athlete Gambling Behaviors and AttitudesEllenbogen, S., Jacobs, D.F., Derevensky, J., Gupta, R. & Paskus, T.S. (2008). Gambling behavior among college student-athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20, 349-362.

Huang, J.H., Jacobs, D.F., Derevensky, J.L., Gupta, R. & Paskus, T.S. (2007). A national study on gambling among U.S. college student-athletes. Journal of American College Health, 56(2), 93-99.

Huang, J.H., Jacobs, D.F., Derevensky, J.L., Gupta, R. & Paskus, T.S. (2007). Gambling and health risk behaviors among U.S. college student-athletes: Findings from a national study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 390-397

Marchica, L. & Derevensky, J. (2016). Fantasy sports: A growing concern among college student-athletes. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 14, 635-645.

Shead, W.N., Derevensky, J.L. & Paskus, T.S. (2014). Trends in gambling behavior among college student-athletes: A comparison of 2004 and 2008 NCAA survey data. Journal of Gambling Issues, 29, 1-21.

St-Pierre, R., Temcheff, C., Gupta, R., Derevensky, J. & Paskus, T. (2014). Predicting gambling problems from gambling outcome expectancies in college student-athletes. Journal of Gambling Studies, 1, 47-60.

Temcheff, C.E., Paskus, Potenza, M.N., Derevensky, J.L. (2016). Which Diagnostic Criteria are Most Useful in Discriminating Between Social Gamblers and Individuals with Gambling Problems? An Examination of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Criteria. Journal of Gambling Studies, 1-12.

Temcheff, C.E., Derevensky, J.L. & Paskus, T.S. (2011). Pathological and disordered gambling: A comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-V criteria. International Gambling Studies, 11, 213-220.

Ncaa Student Athlete Gambling Rules 2019

Read More > about Sports Wagering Publications Using NCAA DataIn the interests of protecting the health and well-being of the hundreds of thousands of student-athletes who participate in college sports, NCAA research studies the behaviors of student-athletes – including behaviors that could put student-athletes at risk – in order for NCAA members to develop legislation, educational policies and best practices that enhance student-athletes’ experiences in college.

One of those behaviors is gambling. The NCAA has had bylaws restricting sports wagering for many years because leaders in college sports believe sports wagering not only threatens the integrity of the game but also is an entry point into other behaviors that may compromise student-athlete health and well-being.

The NCAA has conducted studies on student-athlete gambling behavior every four years since 2004. The most recent in 2016 surveyed more than 22,000 current college athletes across all three NCAA divisions about their attitudes toward and engagement in various gambling activities, including sports wagering. A summary of findings and detailed slides that examine the trends from 2004 to 2016 are also available.

Read More > about NCAA National Study on Collegiate WageringAs part of an ongoing effort to raise awareness and provide more resources and expertise about behaviors that put student-athletes at risk, the NCAA hosted its ninth annual sports-wagering seminar this past October at the national office in Indianapolis to focus on education and monitoring.

Read More > about Compliance Experts Share How to Spot WageringMany people’s gut reaction is to be more horrified by doping than by gambling. The high-profile media attention given to doping in sports trumps that given to gambling, though every four-year class since 1991 has experienced a major point shaving scandal in college sports.

Read More > about Is Gambling Just as Bad as Doping? You Bet It Is.Dr. Jeffrey Derevensky, the director of the International Center for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviors at McGill University in Montreal, has co-authored the 2008 and 2012 NCAA studies on student-athlete gambling behaviors. Following is a Q&A with the world-renowned expert on the subject.

Read More > about Study Author Outlines 2012 Survey FindingsPreliminary results from the latest NCAA study of college student-athlete gambling behaviors and attitudes reflect hopeful news in overall rates of gambling within the student-athlete population but raise concerns in the ever-changing...

Read More > about Latest wagering study shows decrease in gambling activity

The NCAA and the four major professional sports leagues (MLB, NBA, NFL and the NHL) today filed a complaint against New Jersey state officials in federal court in Trenton, NJ seeking to stop the state from implementing sports betting on...